I never set out to run a math education nonprofit. For a long time, I thought I would spend the rest of my life teaching high school math, and for an even longer time, I thought I would end up in academia. But there were small moments along the way pushing me closer and closer towards my current trajectory of bringing recreational math into kids’ lives.

One of these moments happened when I was in grad school for my master’s in math education. I was at a restaurant with some of my teacher friends. I was also working through The Moscow Puzzles, and started telling one of my friends about a specific puzzle. It involved sheep and goats and moving them around so that they swapped places. About halfway through the explanation, I realized that words really couldn’t do the puzzle justice.

We were a large group that night, so I went around to each of our tables and collected the salt and pepper shakers – salt for the sheep and pepper for the goats. I showed my friend how the puzzle worked with my makeshift manipulatives, and instantly, my friend wanted to try to solve the puzzle themselves. It wasn’t long before others in the group noticed what we were doing and wanted to join in on the puzzling. I set up a couple more stations, and we all spent a few minutes playing with salt and pepper shakers trying to solve an old, Russian math problem.

There are three things that I love about this memory:

- It was spontaneous

- It was infectious

- It was math

For many people, math is something that needs to happen in a specific place at a specific time, like a school or university. This moment showed me that doesn’t need to be the case. Math can happen anywhere at anytime with anything.

Deinstitutionalizing math is vital to get more kids to appreciate it. So often, math is viewed as something that is only for the “smart kids” or the “rich kids,” and I believe that this othering phenomenon is because students only experience math within an educational institution that was historically built for a specific kind of child.

If students begin to see their whole world as mathematical, even in something as ordinary and mundane as salt and pepper shakers, they’ll start to believe that they belong in the world of math, because they’re already living in it.

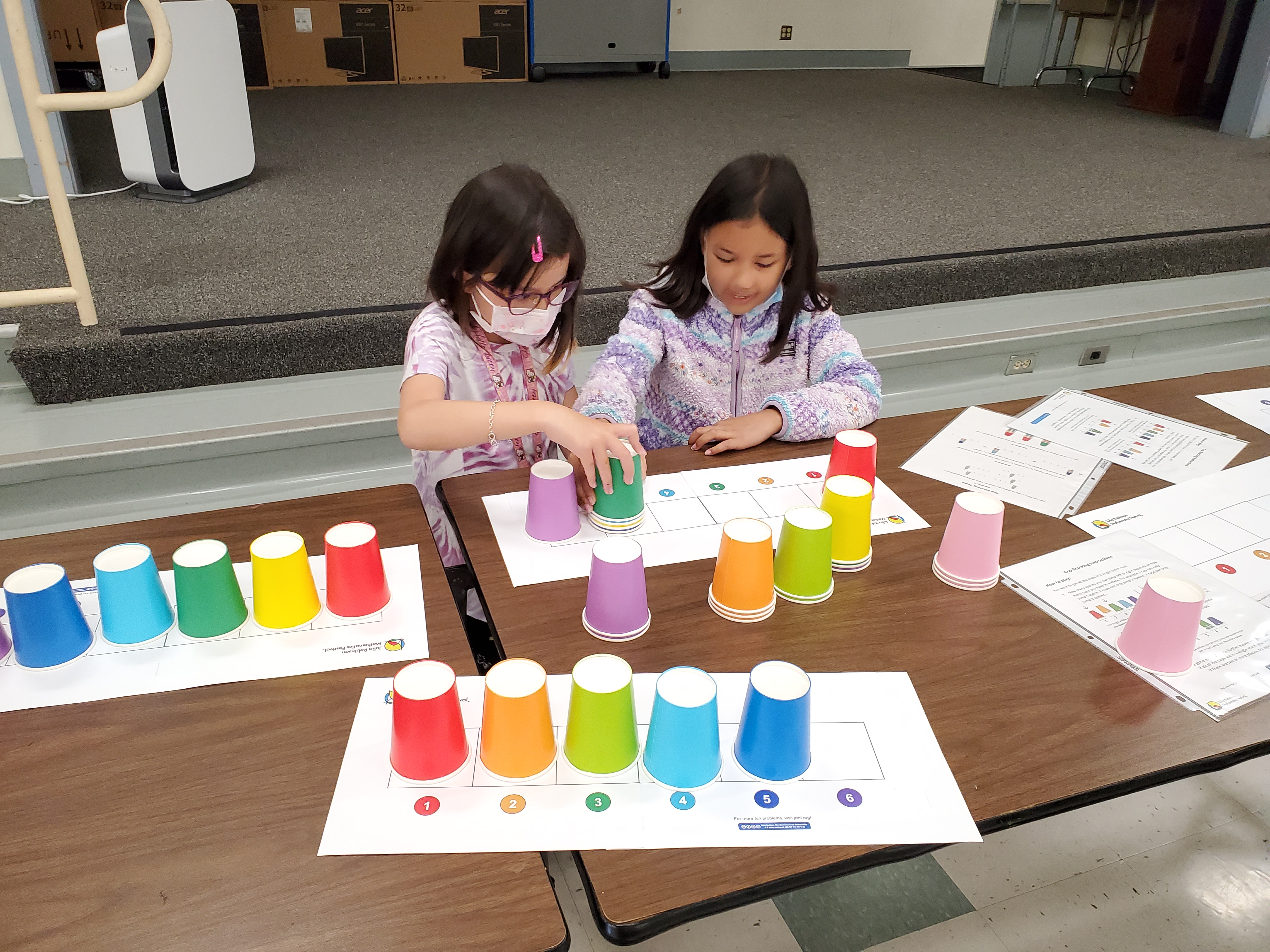

I was fortunate to experience years of recreational math and play with manipulatives before that moment in a Philly restaurant. My dream is that math festivals will begin to provide students with those same kinds of experiences. I believe that a world where kids (and adults) realize they are living in one large math festival is one that would be filled with more critical thinking, curiosity, and beauty.

How do you show kids that the world around them is mathematical? How do you think that math education can shape the average person’s everyday life?